An Ancient Priestly Blessing: A Summary of the Ketef Hinnom Amulets

Intro:

Two small silver amulets were discovered in 1979 in the Ketef Hinnom valley in Jerusalem by archaeologist Gabriel Barkay. Found rolled into tiny scrolls inside a burial cave, they are referred to as the Ketef Hinnom Inscriptions because of the writing found on the amulets. They are quite small at 9.7 × 2.7 cm and 3.9 × 1.1 cm (Yardeni 1991) and are currently on display at the Israel National Museum. The inscriptions are among the most significant archaeological finds related to the Hebrew Bible, since they preserve a form of the priestly blessing. Their discovery provided scholars with rare physical evidence of biblical traditions in use within ancient Judah and continues to be a central point of discussion in the study of Israelite religion and text transmission.

Dating:

The earliest dating (7th to 6th centuries B.C.E) that was suggested by Barkay became the majority view amongst scholars, but did not go without critique, as post exilic views for later dating have been suggested as late as the Hellenistic period 3rd-2nd centuries B.C.E. Johannes Renz and Wolfgang Röllig, in their Handbuch der althebräischen Epigraphik (1995), were skeptical about dating the Ketef Hinnom silver amulets to the late 7th or early 6th century BCE. They argued that the paleographic evidence was too uncertain to fix such an early date securely and suggested that the inscriptions might actually belong much later, possibly as late as the Hellenistic period (3rd–2nd centuries BCE). Their caution set them apart from most scholars, who accept the late pre-exilic/early exilic dating (Renz et. al.,1995). But this view was mostly rejected, even by scholars who pose a revised dating from Barkay such as (Naa’aman 2011) who presented a date for the amulets to the second half of the 6th century–albeit still agreeing these are the earliest examples of biblical texts we have to date. If the majority view is correct that we have biblical material that is 400-200 years older than the Dead Sea Scrolls.

According to Barkay who pushed back at the Hellenistic date offered by Renz, the amulets are indeed confidently dated to the first temple period at the end of the Iron age. He and his team of researchers were able to use innovative photographic imagery to re-examine at an even closer level the epigraphic and paleographic details of the writings. By this new data, along with the stratigraphic context the amulets were found–it is clearly and confidently claimed that the amulets are indeed from the late iron age. Photographic and Computer imaging technology, high resolution digital images have been made and while Barkay admits we cannot be overly precise in dating the inscriptions, the paleographic analysis reinforces the data implications of writing style coinciding with writing of the first temple period citing examples such as various ostraca e.g., Lachish, Arad, Samarian (Barkay 2004). He and his team’s conclusion is that they date from the horizon of the end of the Judaean monarchy-or a paleo-graphic date of the late seventh century B.C.E. to early sixth century BCE.

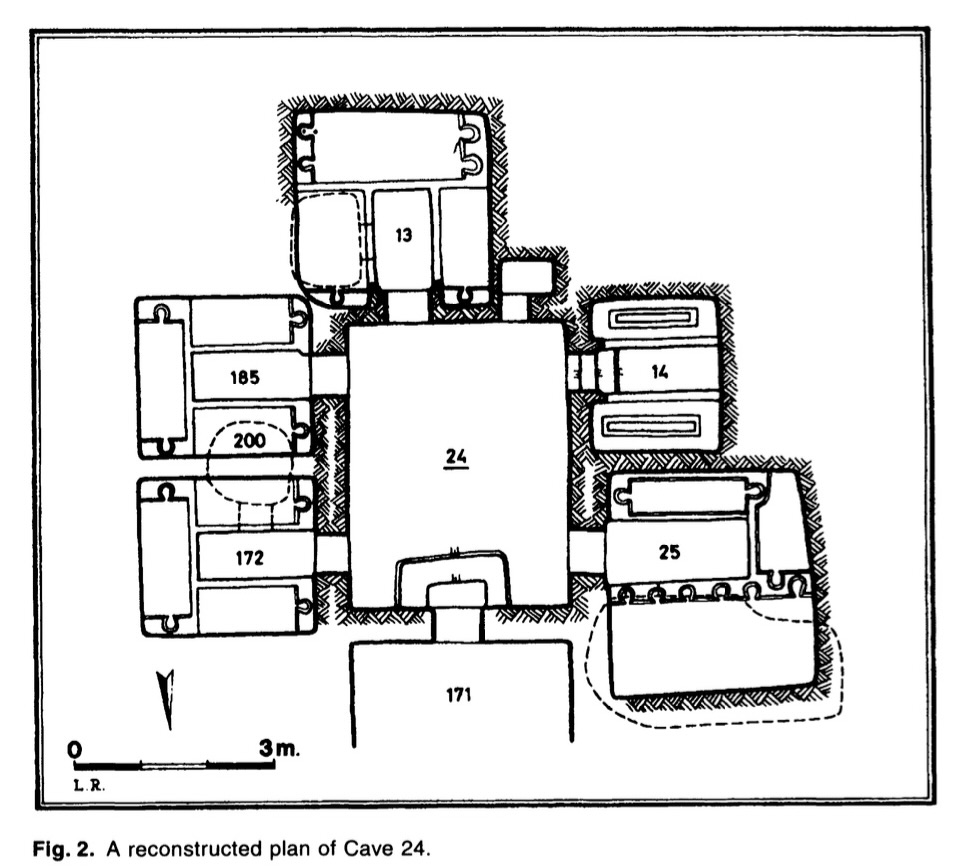

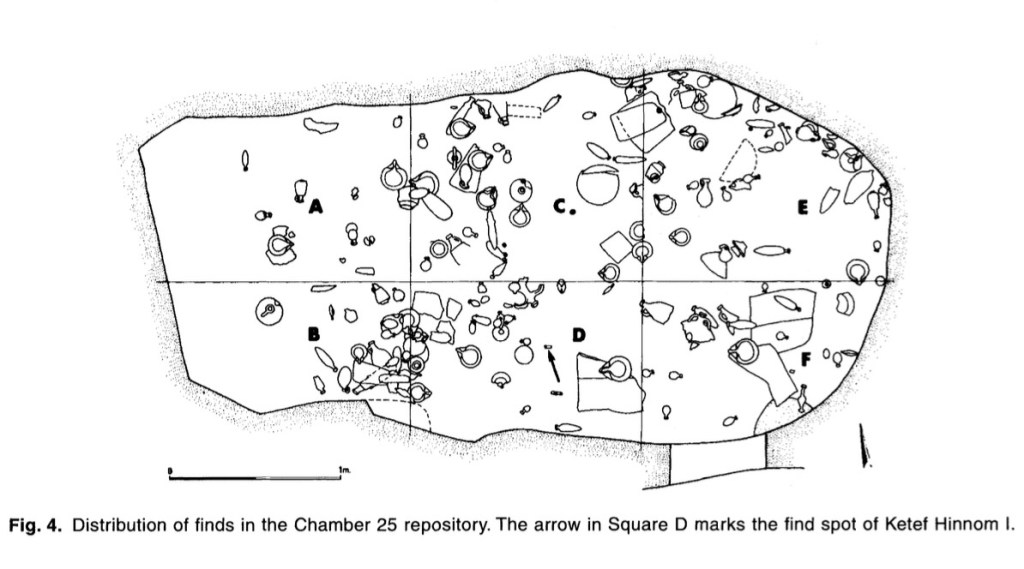

Furthermore, he argues that the plaques were found among deposits inside a repository of what was labeled burial chamber 25, which contained burial shelves with headrests where the bodies were laid until they decomposed. The chambers also contained a repository beneath the main shelf on the right side of the chamber where the bones and other artifacts were later deposited–according to (Barkay 2004) this type of burial chamber is well known from the Iron Age. He also counters Renz’s dating methods which was based on 8 pieces of pottery found that dated to the Hellenistic period (Renz 1995). Since the amount found was so small and found in the upper layers of the deposits, it should not bear the weight for dating the amulets one of which was found in the innermost portion of the repository in chamber 25, and in the lower layers of the deposits (Barkay 2004). Thus, the paleographic data coincide with the archaeological context and support the earlier seventh-sixth century B.C.E. dates proposed originally by Barkay and seconded by Yardeni (Barkay 2004).

Photos below consist of figures 1-4 from (Barkay 2004)

Naʾaman contends that the Ketef Hinnom plaques should be dated to the early Persian period (early fifth century BCE) rather than the late Iron Age. Building on (Berlejung 2008) He argues that silver and gold amulets are virtually absent in Iron Age Palestine but become widespread in the Persian period, particularly under Phoenician influence, where inscribed metal amulets are common (Naa’aman 2011). This cultural context supports a post-exilic date. He further cautions that the archaeological context is incomplete, since not all of the material from the site has been published, making it difficult to reconstruct the full circumstances of the discovery. Moreover, because one of the plaques was found nearer the cave entrance, its placement cannot serve as a reliable basis for dating as (Barkay 2004) has argued for the other. Finally, he cautions that the epigraphic data is somewhat uncertain, which should prevent us from drawing firm conclusions from the inscriptions alone. Beyond these methodological cautions, Naʾaman emphasizes that the plaques are invaluable for understanding religious concepts in early post-exilic Jerusalem. They embody the renewed hopes placed in the rebuilt Temple, the resettlement of the land, and the belief that Israel’s God had orchestrated the return from exile and the redemption of the land (Naa’aman 2011).

Contents and Function:

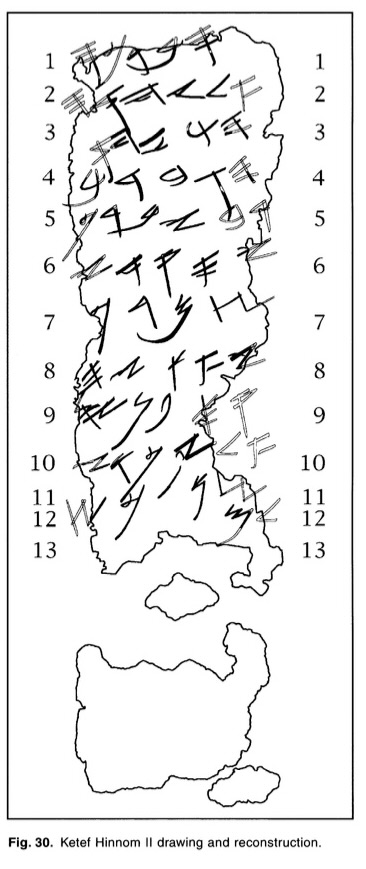

Inscribed in ancient Hebrew script, likely with a stylus no thicker than a human hair, the text of the Ketef Hinnom amulets was exceedingly difficult to decipher, yet what emerged proved remarkable. While the major contents as reconstructed by Barkay (2004) and Yardeni (1991) have been broadly accepted, minor revisions have been proposed in the details of the reading. Nadav Naʾaman closely follows Barkay’s reconstruction but departs slightly in his interpretation of line 11 on Plaque I (see photos for the respective readings of each scholar). Despite such small differences, there is wide agreement that the scribe drew from multiple biblical traditions. For example, lines 3–6 of Plaque I echo passages such as Deuteronomy 7:9 (cf. Dan 9:4; Neh 1:5): האל הגדול והנורא שמר הברית והחסד לאהביו ולשמרי מצותיו. Likewise, the lower portions of both inscriptions preserve a form of the priestly benediction from Numbers 6:24-26, words still recited today in both Jewish and Christian liturgical traditions. Notably, Ada Yardeni was the first to identify and publish the presence of the priestly blessing on these amulets (Yardeni 1991)

יברכך יהוה וישמרך

יאר יהוה פניו אליך ויחנך

ישא יהוה פניו אליך וישם לך שלום

Photos 1-3 consist of (Barkay 2004) transcription and translation of amulets 1-2

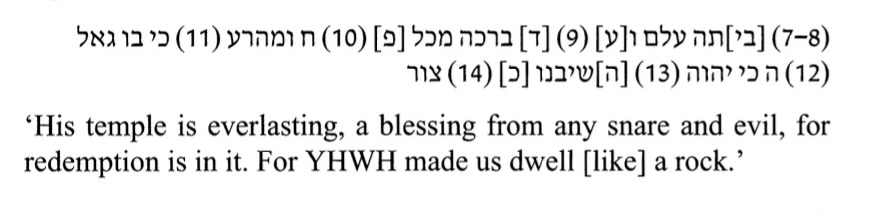

As for their function, beyond serving as a remarkable gift for the deceased who was likely of high status, possibly a priest or a close relative—Barkay interprets the amulets as protective objects, ensuring the blessing of obedience and the eternal security of YHWH even in death. As he writes, “There, their function is apotropaic and/or sanctifying; the inscriptions in these plaques exist as amulets to give their wearers protection against evil in the presence of holiness” (Barkay 2004). By contrast, Nadav Naʾaman, with his revised reading, interprets the text slightly differently. Connecting ביתה (“His Temple”) in line 7 as the subject of כי בו גאל (“For His redemption”), he understands the amulets as proclaiming the redemption of the Temple, recently rebuilt after the exile, and affirming that its blessing is reinstated as a reward for all who are obedient to YHWH and His commandments.

See below (Na’aman 2011) variant reading of plaque 1 lines 7-12

Conclusion:

In conclusion, while the interpretation of the data remains open to scholarly discussion, one thing is certain: the Ketef Hinnom inscriptions offer a remarkable and unparalleled window into the priestly world of the First Temple period. What we hold in these tiny plaques is nothing short of a miracle of preservation. These ancient words, surviving thousands of years through war, exile, and the passage of time, still reach us today, carrying with them the enduring blessing of YHWH.

References

Site Outdoors Photo: Z. Radovan, Jerusalem BAS Library Anatomy of a Judahite Cemetery.

Close up Photos of Amulets & Museum Cave Display: James Linse & Angela Avalos

Barkay, Gabriel, Marilyn J. Lundberg, Andrew G. Vaughn, and Bruce Zuckerman. “The Amulets from Ketef Hinnom: A New Edition and Evaluation.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 334 (May 2004): 41–71. Published by the University of Chicago Press on behalf of the American Schools of Oriental Research.

Naʾaman, Nadav. “A New Appraisal of the Silver Amulets from Ketef Hinnom.” Israel Exploration Journal 61, no. 2 (2011): 184–95.

Renz, Johannes, and Wolfgang Röllig. Handbuch der althebräischen Epigraphik. 3 vols. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1995.

Yardeni, Ada. “Remarks on the Priestly Blessing on Two Ancient Amulets from Jerusalem.” Vetus Testamentum 41, no. 2 (April 1991): 176–85.

Leave a comment