Intro: Water Projects in the Ancient Near East

During the first millennium BCE, kings of the ancient Near East sought to demonstrate their ingenuity and authority through monumental architectural achievements. Rulers of Egypt, Babylon, and Assyria allocated substantial resources to the renovation of temples, the construction of grand palaces, and the development of aqueducts to irrigate royal gardens—all serving as expressions of their divine mandate to honor the gods and ensure that their cities reflected cosmic order and perfection. A prominent example is the Neo-Assyrian king Sennacherib, whose extensive system of canals and aqueducts transformed Nineveh into a visible manifestation of imperial might and divine favor. In contrast, the focus of this study—the water project of King Hezekiah in Jerusalem, known as the Siloam Tunnel—reveals a markedly different motivation. Rather than functioning as a monument to royal prestige, Hezekiah’s tunnel represented a pragmatic and defensive initiative designed to safeguard Jerusalem’s water supply in the face of Assyrian aggression. Considered together, these two undertakings illustrate divergent expressions of kingship: one expansive and propagandistic, the other restrained and faith-driven.

King Sennacherib: The Suzerain of Hezekiah

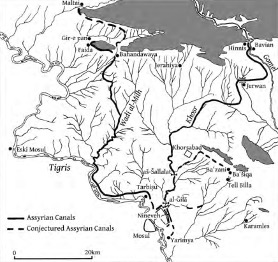

Neo-Assyrian king Sennacherib, was a king who took his role as the proliferator of the gods and their dominionvery seriously. Not only did he construct grand palaces, temples, and gardens in Nineveh, but he also engineered an immense aqueduct and canal system that, as he boasted, brought water from the distant mountains. Through these projects, Sennacherib presented himself as a divine-like benefactor who mastered nature and ensured abundance. Ideologically, he was mimicking the chief Assyrian god Ashur, who provided for his people and ruled the universe.Throughout his reign, Sennacherib engaged in some of the most extensive waterwork programs in all Assyrian history, creating at least sixteen canals that brought constant supply of water to Nineveh (Grayson & Novotny 2014: 24).

Taken from (Grayson & Novotny 2014: 25) Figure 4: Map showing Sennacherib’s canals. Adapted from Reade, RLA 9/5–6 (2000) p. 406 fig. 9.

The Bavian Reliefs appear multiple times on a cliff face carved into panels resembling stelae, each depicting the king alongside his patron gods. While these carvings are often referred to as the Bavian Reliefs, they are technically closer to the village of Ḫinnis (modern Kharusa) where the canal begins—the very canal described in the text. This canal formed part of Sennacherib’s extensive system of waterways and aqueducts designed to supply Nineveh with a steady flow of water throughout the year. Sennacherib claimed that “by the command of Aššur, the great lord,” he personally directed the digging of multiple canals and the great Patti-Sennacherib channel, bringing water from distant mountains to Nineveh. With divine sanction and only a small workforce, he boasted, he transformed arid lands into orchards filled with every kind of fruit tree, vine, and spice, irrigating the fields of his capital. Sennacherib swore by Aššur that he alone had accomplished this feat, completing the canal in little more than a year. The text presents the king as divinely empowered to reshape nature itself, blending technological achievement with theological propaganda (RINAP 3/2 Grayson & Novotny 2014, 310).

Hezekiah’s Water Project in Ancient Israel

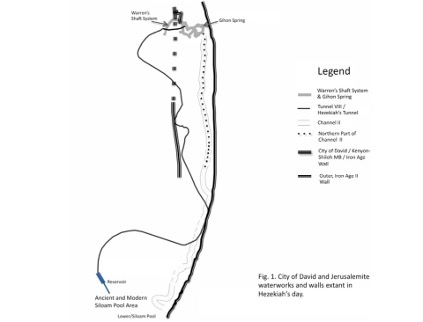

While kings across the ancient Near East (like Sennacherib above) routinely boasted of monumental construction of water canals—there is another subterranean water project that has stood out to historians as uniquely ingenious because of the way it was constructed. Unlike the grand, above-ground architectural displays of Assyria, there is an ancient tunnel that was excavated to redirect the original water supply of Jerusalem. In 1838, American explorer Edward Robinson was the first modern scholar to identify and describe the tunnel. He crawled through the water-filled passage and confirmed that it connected the Gihon Spring to the Pool of Siloam, immediately calling to mind the verses in the Bible that told of King Hezekiah and his channel that he dug. The goal was to stop up the waters flowing through existing tunnels that went outside of the safety of the city fortification walls, redirect the water to the west keeping it inside the city (cf. 2 Kgs 20:20, 2 Chron 32:4). The tunnel would be known from here on as the Siloam Tunnel or Hezekiah’s Tunnel.

והוא יחזקיהו סתם את־מוצא מימי גיחון העליון ויישרם למטה־מערבה לעיר דויד ויצלח יחזקיהו בכל־מעשהו

…this Hezekiah who stopped the source of the upper waters of the Gihon and directed them to the west side of the city of David, and Hezekiah succeeded in all that he did. (2Ch 32:30)

Archaeological and Historical Background

The almost immediate assumption of many bible scholars and archaeologists, was that this discovery was one of the most unique instances where we have the biblical texts being authentically confirmed by not just archaeology, but an ancient inscription along with it–a full package deal it seemed. In his search for archaeological evidence associated with Hezekiah’s reform, Borowski 1995 highlighted material remains from Tel Arad, Tel Beersheba, Tel Lachish, Tel Halif, and Jerusalem (to include the tunnel). He argued that the remains found in destruction layers such as de-commissioned shrines and sanctuaries, the storage and redirecting of food resources, and the constructing of the Siloam tunnel all lined up as means of preparations for rebellion against Assyria. Within this broader context, the Siloam Tunnel in Jerusalem, dated to the late eighth century BCE, emerges as a critical component of the king’s strategic infrastructure designed to secure the city’s water supply in anticipation of Assyrian siege (Borowski (1995, 152–53). Reich and Shukron (2000) proposed a phased development of the Warren’s Shaft water system, identifying its original components, Channel II, Tunnel III, and the rock-cut pool near the Gihon Spring, as dating to the Middle Bronze II period. They emphasized that during this early phase, the natural vertical chimney known as Warren’s Shaft existed geologically but was neither visible nor accessible from the surface or the spring. In the eighth century BCE, workers lowered the floor of the system’s horizontal tunnel, accidentally breaching the upper edge of the shaft—an event evidenced by pottery from that period embedded in the debris. Reich and Shukron interpret this modification as the initial stage of an unfinished engineering plan, which was soon abandoned in favor of a more advanced and comprehensive project: the cutting of a new tunnel to bring water directly into the city, identified as Hezekiah’s Tunnel (Tunnel VIII) (Reich & Shukron 2000, 9).

Yigal Shiloh was comfortable dating the tunnel to the period stating that “A greater number of Iron Age remains contribute to the growing picture. The Siloam tunnel at the foot of the eastern slope may be dated provisionally to the beginning of Iron 11 by circumstantial/stratigraphical considerations alone, e.g., its relationship with Hezekiah’s tunnel” (Shiloh 1979, 170). Cross further argued that Hezekiah’s reforms and related building projects, included the Siloam Tunnel, and that they should be dated to the period of preparation for his revolt against Assyria, rather than to the early years following the fall of Samaria. He followed Albright’s proposed accession date of for Hezekiah 715 BCE and situated Hezekiah’s sixth and seventh regnal years in the years leading up to Sargon II’s death in 705 BCE—precisely when Hezekiah was strengthening Jerusalem’s defenses, reorganizing cultic practices, and consolidating economic resources in anticipation of rebellion. He links the “storage inscription” from Jerusalem to this broader context of fiscal and religious mobilization, noting that biblical and archaeological evidence alike point to large-scale tithing, stockpiling, and administrative activity during this phase of national revival and preparation for Assyrian confrontation (Cross 2001, 46-7).

Some Conflicting Views on Dating

It is important to state that what would become known as the traditional view would not remain unchallenged over the years. While it seems that the traditional Iron Age II date probably still the majority, there is some real debate over the dating of the Siloam Tunnel. John Rogerson and Philip Davies (1996) were some of the first to argue that the Siloam Tunnel was not built by King Hezekiah but several centuries later, most likely during the Hasmonean period. They base their conclusion on three main lines of evidence: archaeology, biblical texts, and paleography. Archaeologically, they contend that the tunnel’s construction fits better within the period when the Siloam Pool was first enclosed by city walls—something that did not occur until Hasmonean times. Biblically, they maintain that no text explicitly attributes a tunnel to Hezekiah; rather, the references in 2 Kings 20:20 and 2 Chronicles 32:30 describe improvements to the earlier Warren’s Shaft system. Paleographically, they argue that the script of the Siloam Inscription could fit either an Iron II or a late Second Temple (Hasmonean) context, and thus cannot be used to prove an eighth-century date. Overall, they conclude that the traditional identification of the tunnel with Hezekiah is based on circular reasoning rather than secure archaeological or textual evidence (Rogerson & Davies 1996, 138-49).

Jane Cahill issued an immediate detailed rejoinder to Rogerson and Davies’ rejection of an Iron Age II date for the Siloam Tunnel, countering their arguments through paleographic analysis of the Siloam Inscription, the archaeological history of the Gihon water systems, and the city’s fortification line. She demonstrated that Iron Age II remains were indeed found by Kenyon (Site F) and Shiloh (Area H) and explained that the tunnel’s construction was necessitated by the intermittent, siphon-like nature of the Gihon spring, whose fluctuating flow required an enclosed system to capture and store excess water—something Warren’s Shaft alone could not accomplish. Thus, while the earlier Siloam Channel lacked strategic function, the later Siloam Tunnel provided a secure and concealed water system essential during siege conditions. Cahill further emphasized that Rogerson and Davies’ arguments reflected a misunderstanding of Jerusalem’s archaeological and hydrological context, noting that newly available radiocarbon analysis of a stalactite from the tunnel ceiling yielded a calibrated date in the eighth century BCE, thereby reinforcing the traditional dating of the Siloam Tunnel to Hezekiah’s reign (Cahill 1997, 184). Even still, the status quo had been challenged, and the debate was on the table.

Shlomo Guil 2017, agreeing with Robinson and Davies, argues for a much later construction date for tunnel VIII or the Siloam Tunnel, based on engineering, archaeological, historical, and even paleographic, and epigraphic evidence from the Siloam inscription. He proposes a Hellenistic date for Tunnel VIII and argues all together that the water provision initiated by Hezekiah was the short tunnel Tunnel VI–not Tunnel VIII. This was the tunnel he dug rapidly after discovering the natural shaft. According to this view, the Siloam Tunnel traditionally associated with Hezekiah may not have been his work, and the emergency tunnel reflects a short-term, urgent construction effort rather than the more celebrated engineering feat of Tunnel VIII (Guil 2017, 153-56).

Additionally, Reich and Shukron have revised their views on the dating of the Siloam Tunnel. In “The Date of the Siloam Tunnel Reconsidered” (2011), they challenge its traditional attribution to King Hezekiah, proposing instead that it was completed several decades earlier—in the early 8th century BCE, possibly during the reign of King Jehoash. Their argument rests primarily on pottery evidence from fills beneath an Iron Age house built over the Rock-Cut Pool, which they date to the late 9th century BCE, as well as on the discovery of a smoothed, blank plaque carved into the rock wall near a tunnel entrance outside the Gihon Spring. They interpret this as the original starting point of the Siloam Tunnel, perhaps intended for an unfinished dedicatory inscription, dating the project to the ninth or early eighth century at the latest. Together, these findings suggest that the tunnel belonged to an earlier phase of Jerusalem’s water system later reused or expanded during Hezekiah’s reign (Reich & Shukron 2011, 150–54). Asher Grossberg, in “How Did Hezekiah Prepare for Sennacherib’s Siege?” argued that the southern part of Channel II was the tunnel that Hezekiah built in anticipation of Sennacherib’s attack, while Tunnel VIII was built after the Assyrian encounter in order to improve the city’s water supply security (Grossberg 2013, 205–18). In response to this, Mary Katherine Yem Hing Hom (2016) argues that the “exceptional conduit” attributed to King Hezekiah in biblical texts can only be identified with Tunnel VIII (commonly known as Hezekiah’s Tunnel or the Siloam Tunnel), not Channel II. While both systems convey water from the Gihon Spring, only Tunnel VIII carries it to the west side of the City of David, matching the biblical description in 2 Chronicles 32:30. She notes that the northern portion of Channel II dates to the Middle Bronze Age and that its Iron Age II extension was relatively unremarkable compared to the sophisticated engineering of Tunnel VIII—a 533-meter tunnel hewn without intermediate shafts, representing a major technological advance. The accompanying Siloam Inscription, though not royal, reflects the pride and craftsmanship of its builders and commemorates this extraordinary feat. Hom therefore concludes that Tunnel VIII alone fits the historical, geographical, and textual criteria for Hezekiah’s tunnel (Yem Hing Hom 2016, 496)

(Figure from Yem Hing Hom 2016, 494 based on Reich and Shukron 1994)

Amihai Sneh, Ram Weinberger, and Eyal Shalev (2010) reevaluated the Siloam Tunnel’s purpose, construction, and dating through geological and hydrological analysis. They argue that the tunnel was built to correct the hydrological shortcomings of the earlier Channel II, which failed to provide sufficient and secure water during Jerusalem’s rapid population growth in the late eighth century BCE. Based on geological evidence, they propose that the tunnel followed natural karstic fissures and cavities, explaining its winding course. Their engineering assessment suggests the project required at least four years to complete—too long to have been an emergency measure against Sennacherib’s siege in 701 BCE. Consequently, they conclude that the Siloam Tunnel was not built by Hezekiah but rather by his son Manasseh in the early seventh century BCE, during a period of political stability and prosperity.

Despite occasional challenges to the traditional Iron Age II dating, the preponderance of archaeological, paleographic, and textual evidence continues to support the identification of the Siloam Tunnel (Tunnel VIII) with King Hezekiah’s waterworks. While some scholars have argued for later Hasmonean or Manasseh-era construction, their claims often rely on reinterpretations of the city’s fortifications, paleography, or Channel II, which fail to account for the tunnel’s advanced engineering, its alignment with the biblical description in 2 Chronicles 32:30, and the associated Iron Age II material. The Siloam Tunnel thus remains a remarkable example of eighth-century BCE Jerusalemite ingenuity, reflecting Hezekiah’s strategic and religiously motivated efforts to secure the city’s water supply.

The Siloam Tunnel Ensured Survival

King Hezekiah’s tunnel represents a feat of practical engineering born out of crisis and necessity. Carved through nearly 533 meters (1,750 feet) of solid bedrock beneath Jerusalem, the tunnel redirected water from the Gihon Spring fortified structure system already in place, to the Pool of Siloam within the city walls, securing Jerusalem’s water supply against the Assyrian threat (2 Kings 20:20; 2 Chronicles 32:30).

וְיֶ֨תֶר דִּבְרֵ֤י חִזְקִיָּ֨הוּ֙ וְכָל־גְּב֣וּרָת֔וֹ וַאֲשֶׁ֣ר עָשָׂ֗ה אֶת־הַבְּרֵכָה֙ וְאֶת־הַתְּעָלָ֔ה וַיָּבֵ֥א אֶת־הַמַּ֖יִם הָעִ֑ירָה הֲלֹא־הֵ֣ם כְּתוּבִ֗ים עַל־סֵ֛פֶר דִּבְרֵ֥י הַיָּמִ֖ים לְמַלְכֵ֥י יְהוּדָֽה (MT).

And the rest of the acts of Hezekiah and all his might of which he made the pool and the tunnel; and brought in the water of the city, are they not written upon the Book of the Days of the Kings of Judah? (2Ki 20:20)

וַיִּקָּבְצ֣וּ עַם־רָ֔ב וַֽיִּסְתְּמוּ֙ אֶת־כָּל־הַמַּעְיָנ֔וֹת וְאֶת־הַנַּ֛חַל הַשּׁוֹטֵ֥ף בְּתוֹךְ־הָאָ֖רֶץ לֵאמֹ֑ר לָ֤מָּה יָב֨וֹאוּ֙ מַלְכֵ֣י אַשּׁ֔וּר וּמָצְא֖וּ מַ֥יִם רַבִּֽים

“and there was a great assembly of people, and they stopped all the springs and the stream that flowed inside the earth, saying, “Why should the kings of Assyria come and find much water?” (2Ch 32:4)

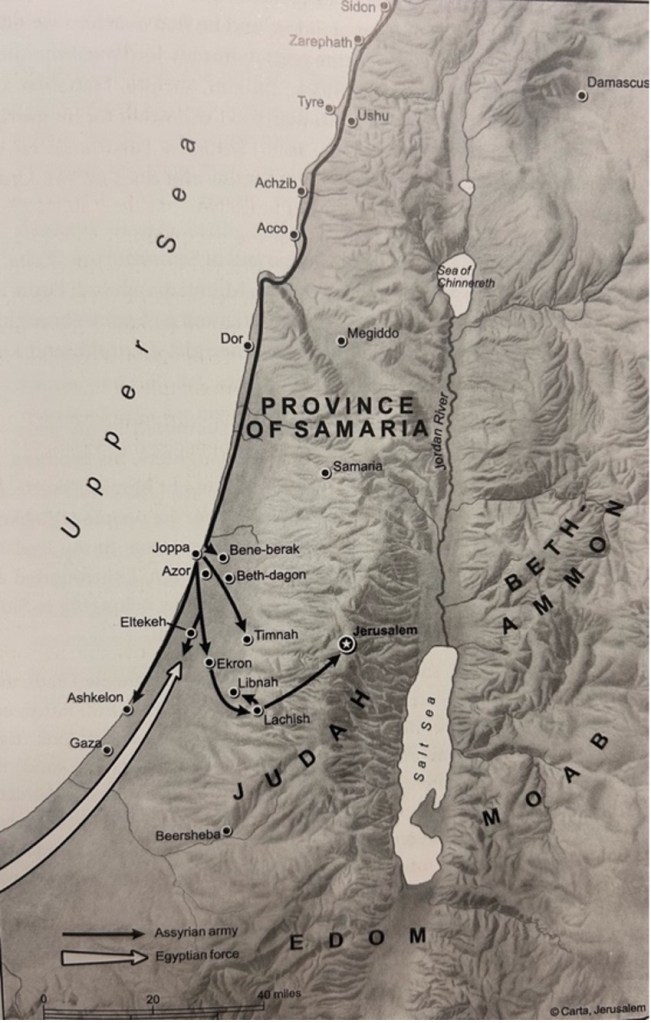

Along with the extensive amounts of archaeological evidence from the destruction layers at multiple sites throughout Israel, there are also external written sources from Mesopotamia that shed light on the kind of oppositional environment Hezekiah faced. According to Sennacherib’s

royal inscriptions, starting with the first the Rassam Cylinder, followed by the various Prism copies, the Assyrian king claims to have laid severe siege upon the region during his third campaign of 701, squashing the rebellions in the west beginning with Syria, then moving south along the coast all the way down to Ashkelon–capturing cities, taking captives, and removing rulers one by one (Cogan 2008, 126-35). Eventually the king went after the territory of Judah, destroying the important site of Lachish and even laying siege on Jerusalem, because Hezekiah was seen as a leading force in the rebellion as shown by his overrunning of the Philistines who were allies of the Assyrians (2 Kgs. 18:8). With Sennacherib defeating all leaders in the region, and even Egyptian allies who came to the aid of Ekron, one could only imagine what he had planned for the king of Jerusalem.

“As for him (Hezekiah), I confined him inside the city of Jerusalem his royal city, like a bird confined inside a cage. I set up blockades against him and made him dread exiting his gate. I deteatched from his land the cities that I had plundered and I gave them to Mitinti, the king of the city Ashdod, and Padî, the king of Ekron, and Silli-Bēl, the king of the land of Gaza, (and thereby) made his land smaller. To the former tribute, their annual giving, I added the payment of gifts (in recognition) of my overlordship and imposed (it) upon them” Rassam Cylinder lines 52-54 (Grayson & Novotny 2012, 65).

Map op of Sennacherib’s third Campaign (Cogan 2008, 123)

The Hubristic king goes on to say how he forced Hezekiah to pay massive amounts of tribute in a fearful dread for breaking their Suzerain Vassal relationship–and while Sennacherib’s scribes go out of their way to make the Judean king to look as weak and defeated as possible, there a few interesting points that make Biblical scholars and historians raise a few questions. For example, why does Sennacherib seem to be bent on removing and replacing some rebels in the region but not Hezekiah? According to the Rassam Cylinder lines 32-48, Luli king of Sidon, and Sidqa king of Ashkelon are both deposed and replaced by loyal vassals Sennacherib even goes as far as reinstating Padi, the king of Ekron back into power, after his own people had given him up handing him over to Hezekiah (Grayson & Novotny 2014, 63-65). Furthermore, even though the king says he shut Hezekiah up in Jerusalem “like a bird in a cage,” he does not record fully capturing the city–a sharp departure from standard Assyrian policy toward rebellious vassals, and a leader of rebellion no less! The biblical accounts (2 Kings 18–19; 2 Chron 32; Isa 36–37) likewise describes a siege but no full conquest, claiming divine deliverance from YHWH. These are not new questions, commentators Kalimi (2014, 38–39) notes that Jerusalem appears to have been subjected to a form of blockade rather than a full-scale siege equipped with the usual military machinery.

Unlike other Judean cities that were captured and destroyed, the Assyrian records describe Jerusalem differently, and curiously, the palace reliefs at Nineveh depict the siege of Lachish rather than that of Jerusalem—the royal city of Hezekiah. This omission is striking given Jerusalem’s political importance. Cogan (2014, 70–71) builds on the insights of Tadmor, Millard, and Gallagher, who each point out the peculiarities of Sennacherib’s account. Tadmor suggested that the unusually extensive booty list functioned as a kind of “literary compensation” for Sennacherib’s failure to capture Jerusalem or depose Hezekiah, outcomes that would have been expected in the standard “canonical model” of Assyrian conquest narratives. Millard and Gallagher likewise describe the account as reflecting an “incomplete victory,” in which the scribes amplified Judah’s suffering and detailed the tribute to mask the absence of a decisive conquest. Cogan concludes that this deviation from typical Assyrian procedure—particularly the decision not to provincialize Judah—reflects a broader imperial policy under Sennacherib. Unlike his father, Sennacherib was not aggressively expansionist; rather, his approach was to maintain a humbled Hezekiah as a loyal vassal, representing a new model of Assyrian control rather than an outright annexation.

While the Biblical writers certainly attribute the survival of Jerusalem to YHWH and divine deliverance, could also be that the preparation through his reform and redistribution of goods to Jerusalem, along with the completion of Hezekiah’s tunnel ensured a steady internal water supply from the Gihon Spring, effectively neutralizing one of the key siege tactics of the ancient world: cutting off access to water. This innovation may have transformed what could have been a swift defeat into a prolonged standoff, compelling Sennacherib to receive tribute rather than annihilate. In this light, Hezekiah’s tunnel was not merely an engineering marvel but a strategic act of survival. It provided the infrastructural means for Jerusalem’s endurance and may have directly contributed to the preservation of the Davidic monarchy now when it was most vulnerable.

Conclusion

In an age when monumental works often celebrated divine kingship and ritual grandeur, Hezekiah’s tunnel stands apart as a project of faith, foresight, and engineering brilliance, arguably one of the most astonishing achievements of the ancient world. While the biblical account emphasizes Jerusalem’s miraculous deliverance from the Assyrian threat through the angel of YHWH, this subterranean passage reveals how faith and practical action were not opposing forces but deeply intertwined in Hezekiah’s reign. His preparation for Sennacherib’s campaign, channeling the Gihon’s waters within the city walls, was both a strategic and a theological act, embodying trust in divine protection expressed through human ingenuity.

Unlike Sennacherib’s aqueducts and canals, which glorified imperial power and divine kingship, Hezekiah’s tunnel reflected a humbler yet profound theology: that covenantal faith must be lived out through wise and decisive action. By safeguarding Jerusalem’s lifeline, Hezekiah demonstrated that genuine faith does not dismiss human responsibility but sanctifies it. In this way, the Siloam Tunnel was more than an engineering feat; it was a material expression of belief. A silent witness to a king’s conviction that divine deliverance often flows through human hands prepared in faith.

Bibliography

Amim, O. Muhammed.

2018. “The Siloam Inscription from Jerusalem.” World History Foundation. WorldHistory.org.

Borowski, Oded.

1995. “Hezekiah’s Reforms and the Revolt against Assyria.” The Biblical Archaeologist 58 (3): 148–55. Published by the University of Chicago Press on behalf of the American Schools of Oriental Research.

Cahill, Jane M.

1997. “A Rejoinder to ‘Was the Siloam Tunnel Built by Hezekiah?’” The Biblical Archaeologist 60 (3): 184–85. Published by the University of Chicago Press on behalf of the American Schools of Oriental Research.

Cogan, Mordechai.

2008. The Raging Torrent: Historical Inscriptions from Assyria and Babylonia Relating to Ancient Israel. Jerusalem: Carta.

2014. “Cross-Examining the Assyrian Witnesses to Sennacherib’s Third Campaign: Assessing the Limits of Historical Reconstruction.” Pp. 51–74 in Sennacherib at the Gates of Jerusalem: Story, History and Historiography, ed. Isaac Kalimi and Seth Richardson. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East 71. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

Cross, Frank Moore.

2001. “A Fragment of a Monumental Inscription from the City of David.” Israel Exploration Journal 51 (1): 44–47. Published by the Israel Exploration Society.

Grayson, A. Kirk, and Jamie Novotny.

2012. The Royal Inscriptions of Sennacherib, King of Assyria (704–681 BC), Part 1. Royal Inscriptions of the Neo-Assyrian Period 3/1. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

2014. The Royal Inscriptions of Sennacherib, King of Assyria (704–681 BC), Part 2. Royal Inscriptions of the Neo-Assyrian Period 3/2. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

Grossberg, Asher.

2013. “A New Perspective on the Southern Part of Channel II in the City of David.” Israel Exploration Journal 63 (2): 205–18. Published by the Israel Exploration Society.

Guil, Shlomo.

2017. “A New Perspective on the Various Components of the Siloam Water System in Jerusalem.” Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 133 (2): 145–75. Published by Deutscher Verein zur Erforschung Palästinas.

Hom, Mary Katherine Yem Hing.

2016. “Where Art Thou, O Hezekiah’s Tunnel? A Biblical Scholar Considers the Archaeological and Biblical Evidence concerning the Waterworks in 2 Chronicles 32:3–4, 30 and 2 Kings 20:20.” Journal of Biblical Literature 135 (3): 493–503. Published by the Society of Biblical Literature.

Kalimi, Isaac.

2014. “Sennacherib’s Campaign to Judah: The Chronicler’s View Compared with His Biblical Sources.” Pp. 11–50 in Sennacherib at the Gates of Jerusalem: Story, History and Historiography, ed. Isaac Kalimi and Seth Richardson. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East 71. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

Norin, Stig.

1998. “The Age of the Siloam Inscription and Hezekiah’s Tunnel.” Vetus Testamentum 48 (1): 37–48. Published by Brill.

Reich, Ronny, and Eli Shukron.

2000. “The System of Rock-Cut Tunnels Near Gihon in Jerusalem Reconsidered.” Revue Biblique 107 (1): 5–17.

2011. “The Date of the Siloam Tunnel Reconsidered.” Tel Aviv 38: 147–57.

Rogerson, John, and Philip R. Davies.

1996. “Was the Siloam Tunnel Built by Hezekiah?” The Biblical Archaeologist 59 (3): 138–49. Published by the University of Chicago Press on behalf of the American Schools of Oriental Research.

Shiloh, Yigal.

1979. “City of David: Excavations 1978.” The Biblical Archaeologist 42 (3): 165–71. Published by the American Schools of Oriental Research.

Young, Ian, and Robert Rezetko.

2008. Linguistic Dating of Biblical Texts: An Introduction to Approaches and Problems. Vol. 1. London: Equinox. Kindle edition.

Leave a comment