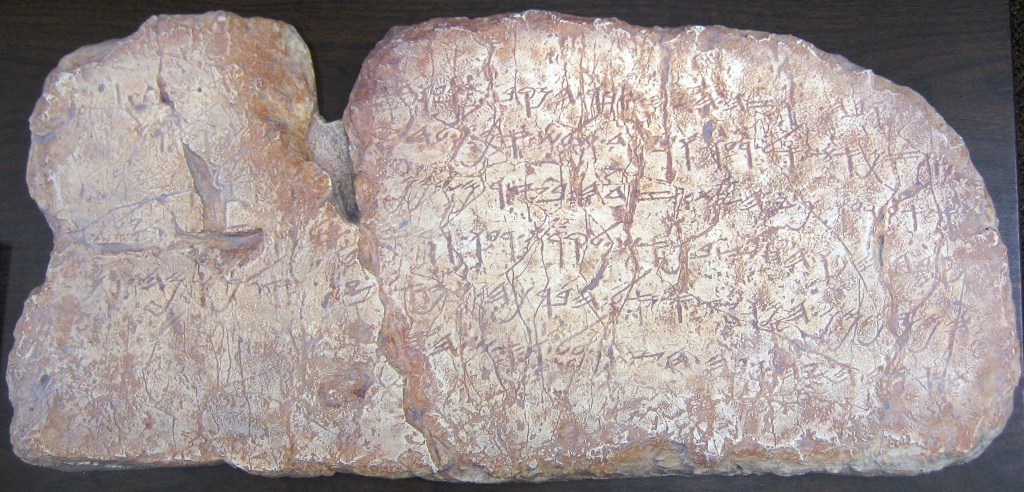

The history of Hezekiah’s tunnel has proven to be an amazing archaeological feature from ancient Jerusalem that gives us a glimpse into the world of ancient Israel and Biblical History. King Hezekiah, preparing for the Assyrian invasion, left behind a project that would echo of his innovative initiative for defense of the city, that would echo throughout generations to come. Yet, there is yet another remarkable feature related to this tunnel that we have yet to discuss–that is none other than the infamous Siloam Inscription. In 1880, while he was wading through the Siloam tunnel, 16-year-old Jacob Eliyahu noticed lines of writing imbedded in the rock of the tunnel. Unbeknownst to Jacob Eliyahu, the inscription he uncovered would later be recognized as one of the most important ancient Hebrew texts, providing invaluable insights into the engineering achievements and linguistic development of early Jerusalem. The writing was carved into the tunnel wall now known as the Siloam Inscription (Norin 1998, 38). In 1890, it was removed from the tunnel and sent to Istanbul Turkey, where it remains in the Istanbul Archaeological Museum. During the removal from the tunnel wall, the inscription broke into six pieces, but the text was repaired based on a squeeze taken shortly after its discovery. Below is a photo of the original inscription on display at the museum in Turkey. The writing of the inscription is still known as one of the earliest examples of Hebrew writing.

Fig 1. Siloam Inscription (from Shakir Muhammed Amin 2018)

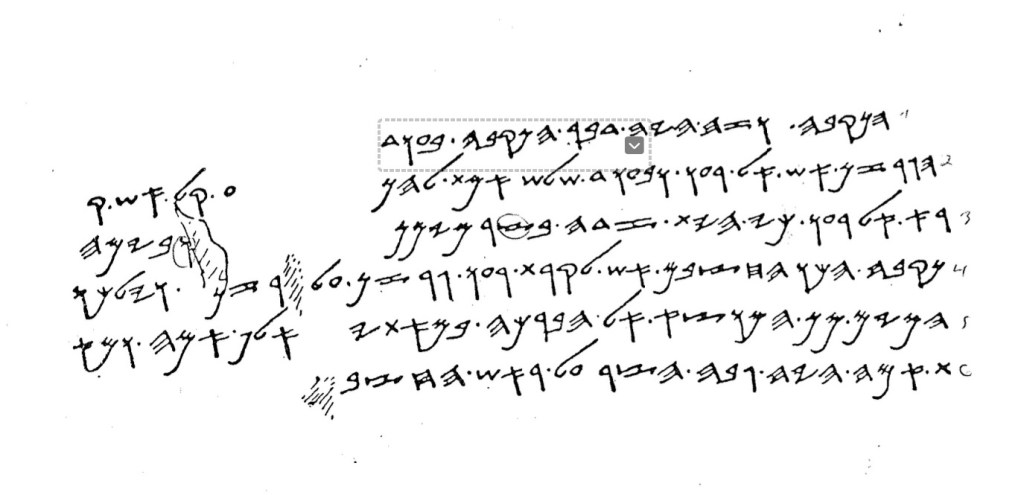

The inscription was found carved in at the end of the tunnel as a memorial and was completed by the excavators of the tunnel project. It describes the miraculous undertaking of the project’s task, where two teams of diggers pursued cutting into the bedrock from opposite sides–one from the north and the other from the south. This is quite an amazing accomplishment, especially when one considers the curvature of the S shaped tunnel. The achieve is nothing short of engineering genius. Additionally, the Siloam Inscription is exceptionally significant because it provides a direct textual witness that complements the archaeological evidence. Together, the inscription, the tunnel itself, and the biblical accounts (2 Kings 20:20; 2 Chronicles 32:30) offer multiple independent records of the same historical event. Later intertestamental writings such as Ben Sira (Sirach 48:17), preserved among the texts found at Masada, continue to attest to the tunnel’s purpose and function. Collectively, these sources make the construction of Hezekiah’s tunnel one of the best-documented events in biblical history. Ultimately, the significance of the inscription extends beyond its role as a historical witness; its content, when analyzed through epigraphic and linguistic studies, provides valuable evidence for determining its date.

Paleography & Script Style

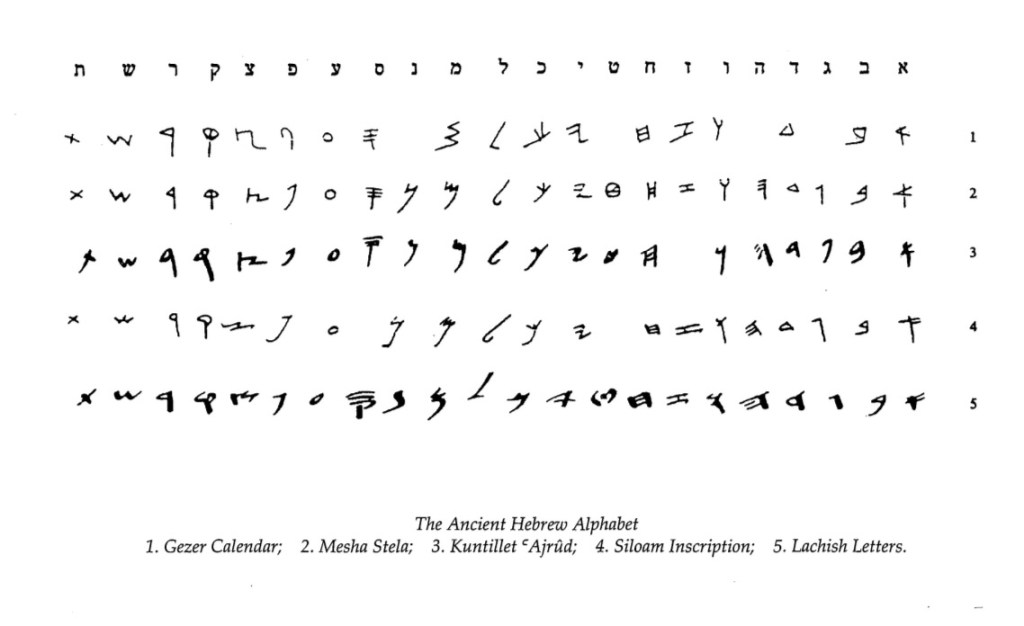

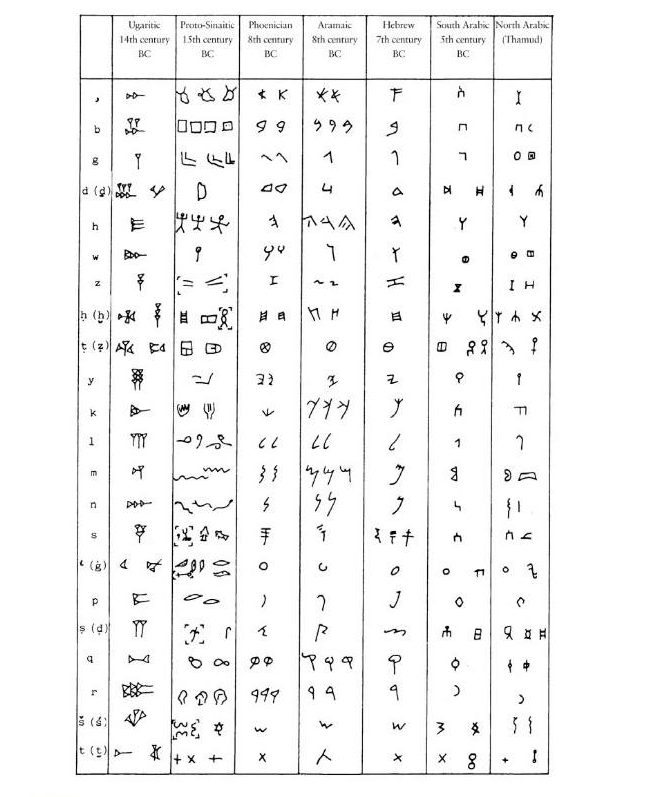

The style of writing in the Siloam Inscription plays a key role in discussions about the inscription itself, and by extension, the dating of the Siloam tunnel; through one crucial tool– paleography. Paleography, which is the study of ancient scripts, enables scholars to estimate the age of texts by analyzing the development and characteristics of letter forms and writing styles over time. The writing is in Paleo-Hebrew script, which traces its origins back to what scholars refer to as the Proto-Canaanite script. This early writing system represents the first true alphabet, distinct from logographic and syllabic systems like those used in Akkadian and Egyptian. Although Ugaritic also employed an alphabetic system, it retained cuneiform-style signs. In contrast, Proto-Canaanite used pictographic symbols, each representing a specific sound or letter. The earliest known examples of this script have been discovered in Egypt, at sites such as Wadi el-Hol and Serabit el-Khadem in the Sinai Peninsula. Because of their location, these inscriptions were initially labeled “Proto-Sinaitic.” However, scholars now recognize that this alphabetic tradition later reemerged and evolved in Canaan, eventually giving rise to the Phoenician script and, subsequently, Ancient Hebrew, what became Paleo-Hebrew. As a result, the term “Proto-Canaanite” is now considered more accurate. Over time, the script continued to develop, and the style of writing seen in the Siloam Inscription represents a later stage of this long tradition, covering a broad chronological range from the First Temple period through the Hasmonean period. Comparable inscriptions that predate the Siloam Inscription include the Gezer Calendar, the Moabite Stele of King Mesha, and the Kuntillet Ajrud inscriptions (ca. 800 BCE). These follow earlier examples such as the Samaria Ostraca from the first half of the eighth century BCE. From the late eighth into the seventh century BCE, there is a noticeable increase in inscriptions from Judah, including stamp seals and seal impressions, which provide much larger corpora for paleographic study (Ahituv 2008, 2).

Fig 2. Evolution of Ancient Hebrew during the Monarchic Period (from Ahituv 2008, 16)

Fig. 3 Diffusion and Evolution of the Alphabet in the Semitic World (from fig 22.5 Liverani 2014, 393)

Fig. 4 Copy of the Inscription Squeeze (From Ahituv 2008:21)

Dating & Debates

When Hebrew linguists and paleographers compare the Hebrew of the Siloam Inscription to other Ancient Hebrew inscriptions, the majority consensus is that it belongs to the end of the eighth century, which lines the inscription up perfectly to the timeline of Hezekiah and his construction of the tunnel. There are scholars who have argued that the Hebrew script aligns closer to later paleo Hebrew such as that of the scrolls of Qumran, specifically 4QExodusm see (Rogerson & Davies 1996, 145-47) but again, the majority view has always been to date its writing to the late the eighth early seventh centuries BCE (Ahitv 2008, 22, Cross 2001, 44, Norin 1998, 46-48, Hendel 1996, 233-36, Young and Rezetko 2015, 49). In his rejoinder to (Rogerson and Davies 1996) Hendel goes as far as stating “It is in fact quite easy to tell that the script of the Siloam Inscription belongs to the eighth-seventh century sequence and not to the paleo-Hebrew sequence of the Hasmonean era and later” (Hendel 1996, 233). Building on Hendel’s work, Stig Norin critiques Rogerson and Davies’ assertion that certain linguistic features such as the presence of medial vowels, serve as reliable indicators of a Hasmonean-period date. Norin contends that this usage is contentious and offers limited evidence (Norin 1998, 46).

Translation & Language Features

The literary style of the inscription is very biblical and is comparable to the books of historical accounts such as Deuteronomy, Kings or Chronicles (Ahituv 2008, 22). The following transcription is taken from Ian Young and Robert Rezetko’s Linguistic Dating of Biblial Texts Volume 1An introduction to Approaches and its Problems. Note the brackets, which are left for interpreters to fill in, and also, while it is not reflected here there are dots between each word on the inscription. Further note that while this transcription includes sofit (final) letters at the ends of words, in the actual inscription—and in all inscriptions from this period, final letters do not appear as they were not in use yet. I will provide my personal English translation based on this transcription below.

Fig. 5 Hebrew Transcription of Inscription (from Young and Rezetko 2015, 49).

“This is the tunnel, and this is the matter of the cutting; while the excavators are lifting the axe, a man to his friend until three more cubits to be pierced, the voice of a man calling to his friend was heard. because there was (a fissure?) in the rock from the south and from the north, and on the day of the piercing the excavators hit one man to meet his friend, axe upon axe, and the waters went from the source to the pool in 1,200 cubits and 100 cubits was height of the rock above the head of the excavators” (Avalos 2025).

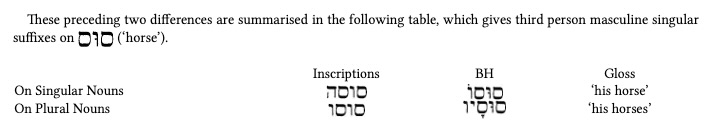

The Inscription begins with the word הנקבה wich is a rare word not attested in Biblcial Hebrew. The root נקב is used as a verb meaning to pierce or break through, and there is a debate if this word here in the inscription is a noun or verb. If it is a noun then it reflects the feminine singular ending ה and is used in the place of תעלה “tunnel” see, 2 Kgs 20:20 (Ahituv 2008, 23; Young and Rezetko 2015, 50). Young and Rezetko also note that if הנקבה is a Niphal verb then the ה can be either a feminine or masculine third person suffix “its tunneling” or “the breaking through.” They explain that during the monarchic period, inscriptions regularly used ה for both masculine and feminine third-person singular suffixes, unlike the later biblical texts where ו became standard for the masculine suffix. This earlier spelling created ambiguity between masculine and feminine forms, which the biblical scribes later resolved by introducing ו (and יו for plural nouns) to distinguish masculine singular and plural suffixes more clearly. Traces of ה being used for the third person masculine singular suffixes can still be found in Archaich Biblical Hebrew (Young and Rezetko 2015, 50-51). See the following table from Young & Rezetko 2015 for a helpful insight of the discussion.

Fig. 6 (from Young and Rezetko 2015, 50-51)

The next sentence וזה היה דבר seems to be a line taken straight out of the bible in style, specifically the book of Deuteronomy or kings as noted by (Ahituv 2008, 23) who mentioned (Deut 15:2, 19:4, 1 Kgs 9:15) for comparisons. Following this sentence is the word בעוד “until.” While one may ask what is so interesting about this simple word, it is actually just one example of a larger discussion around the use of matres lectionis (lit. …mother of reading) which is refers to the vowel letters. The central question regarding letters like vav ו, and yod י in the inscription is whether or not these letters are even vowels at all–especially when they apprear in the middle of words. In other words, when these letters appear in the middle of words, they may not represent vowels at all but rather consonantal diphthongs. Thus, words like בעוד inscription would be pronounced beʿowd in the inscription rather than בְעוֺד beʿôd, in the Masoretic Text.

Make no mistake, there is no question that the inscription contains the use of vowel letters at the end of words—for example, the זה, כי, and חכו (Young & Rezetko 2015, 51). The debated issue concerns vowel in the middle of word–and in some cases ו at the end of certain words. Some scholars argue that they are in fact not vowels but they are pronounced diphthongs because it is commonly accepted that during the First Temple period, Hebrew inscriptions were written almost entirely with consonants only. Vowel letters like aleph א he ה, vav ו, and yod י being rarely usedexcept for at the end of words with clear vowel like function. Some scholars have suggested that there were no vowels used in the Hebrew language up to the 10th century and early monorchic period and they didn’t appear consistantly until later the later post exilic period (Cross and Freedman 1952, 57). As the orthography of Hebrew inscriptions evolved over time later inscriptions show a gradual emergence of these letters eventually in internal positions (Ahituv, Garr, and Fassberg 2019, 55). The use of vowel letters gradually increased over time and amazingly the inscriptions reflect a slow evolution in Hebrew orthography (Ahituv 2008, 2–3). In the case of our inscription, the evidence is somewhat ambiguous and may reflect either a distinct register or dialect of monarchic Hebrew—perhaps one associated with the royal precinct, or an evolving transitional stage in the development of the language. Either way, its pretty fascinating stuff!

Next we have the word רעו (“his companion”) in line 2 and is known from BH. Yet what is unusual is that Biblical Hebrew almost always spells this word as רעהו, with a ה before the waw. Its spelled 117 times, in fact—and only once as רעו (Jer 6:21). What can we make of this phenomenon? First, as we will see, that while the spelling in the Siloam Inscription, is quite rare scholars generally agree that this is not merely a shortened or misspelled form–rather it reflects an older or slightly different grammatical pattern than that of later Biblical Hebrew. Some suggest it preserves an older morphology in which the final yod of the root was still active, influencing how suffixes were attached Others think the waw here may actually represent a plural suffix (“their companion”). In any case, the form רעו stands in sharp contrast to the normal Biblical Hebrew רעהו. Additionally, some scholars propose that the waw here also functions not as a vowel letter but as a another exmaple of a consonantal diphthong, indicating a pronunciation like reʿow. More examples of these diphtongs are in the words like מות in the and mâwēt “death” rather than môt מוֺת and המוצא potentially rendered as ha-môwtza “the spring.”

Other linguistic elements that make the inscripton interesting are the various examples of defective spelling and more ambiguis hebrew words. For example, זדה is a words virtually unatested anywhere in BH or inscritpions, but scholars have related it to a fissure or crack in the wall that allowed the excavators to navigate (Ahituv 2008, 23). In the Siloam Inscription forms such as אש vs. איש “man” in the Masoretic Text, קל vs. קול “voice”, and לקרת vs. לקראת“towards.” The latter is particularly interesting because the form לקרת in line 4 of the inscription differs from the standard Biblical Hebrew spelling לקראת. Scholars have proposed several explanations for this variation. (Young and Rezetko 2015, 52) suggest that לקרת may derive from the root קרה “to meet” or “to happen” rather than קרא “to call” unless the final aleph has simply been dropped. In contrast, (Ahituv 2008, 23) argues that לקרת represents the original and proper form, derived from the root קרי, while the later biblical form לקראת reflects contamination with the similar root קרא. Additional examples of words lacking internal vowel letters include ובים for יום “day” מימן for מימין, “from the right” שלש (for שלוש, “three”), and החצבם for החצבים, “the stonecutters.” Another interesting case is הית, which would normally be pronounced hāytāh “she was” but here may have been pronounced hāyāt, preserving an earlier or more phonetic form.

Conclusion: Why it Still Matters

Although certain linguistic details remain open to debate, and no translation of this First Temple–period Hebrew text can claim absolute certainty in every section of the inscription, scholars largely agree on the unambiguous portions. The consensus reveals that the Siloam Inscription is remarkably clear and provides a rare window into the early development of Hebrew morphology, orthography, and vocabulary. This linguistic evidence, combined with the archaeological record, reinforces the reliability of “the writing on the wall” and the historical authenticity of the biblical narrative. Beyond its linguistic and historical value, the inscription attests to the ingenuity of ancient Jerusalem’s engineers. The tunnel remains a testament to their mastery of surveying, geometry, and acoustic coordination under immense practical challenges. Together, the text and the tunnel form a living bridge between language, archaeology, and the biblical world—a reminder that the stones of Jerusalem still speak to us today.

Bibliography

Ahituv, Shmuel.

2008. Echoes from the Past: Hebrew and Cognate Inscriptions from the Biblical Period. Translated by Anson F. Rainey. Jerusalem: Carta.

Ahituv, Shmuel, W. Randall Garr, and Steven E. Fassberg, eds.

2019. A Handbook of Biblical Hebrew, Volume 1: Periods, Corpora, and Reading Traditions. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

Cross, Frank Moore.

2001. “A Fragment of a Monumental Inscription from the City of David.” Israel Exploration Journal 51 (1): 44–47.

Cross, Frank Moore, Jr., and David Noel Freedman.

1952. Early Hebrew Orthography: A Study of the Epigraphic Evidence. American Oriental Series 36. New Haven, CT: American Oriental Society.

Hendel, Ronald S.

1996. “The Date of the Siloam Inscription: A Rejoinder to Rogerson and Davies.” The Biblical Archaeologist 59 (4): 233–37.

Liverani, Mario.

2014. The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. Trans. Soraia Tabatabai. London and New York: Routledge.

Norin, Stig.

1998. “The Age of the Siloam Inscription and Hezekiah’s Tunnel.” Vetus Testamentum 48 (1): 37–48.

Rogerson, John, and Philip R. Davies.

1996. “Was the Siloam Tunnel Built by Hezekiah?” The Biblical Archaeologist 59 (3): 138–49.

Young, Ian, and Robert Rezetko.

2015. Linguistic Dating of Biblical Texts: Volume 1 – An Introduction to Approaches and Problems. London and New York: Routledge.

Leave a comment