Intro:

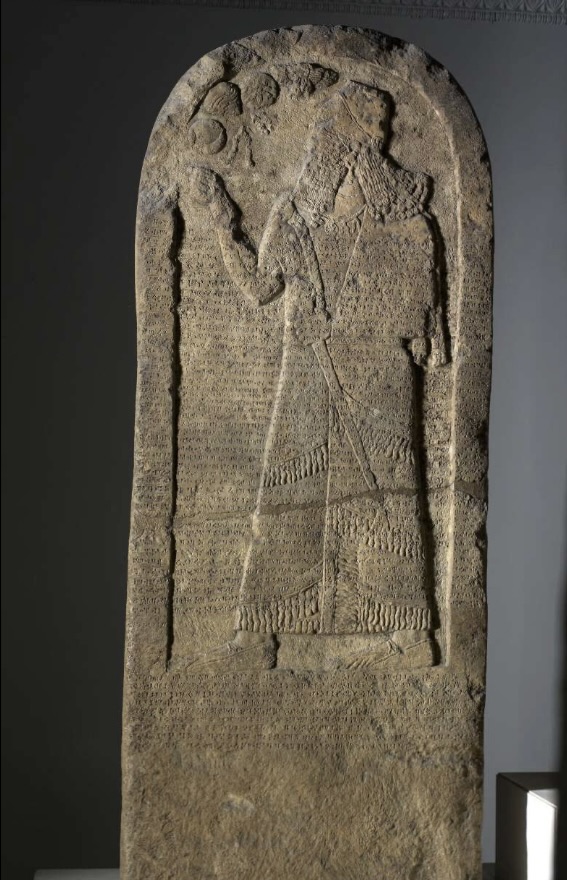

The Kurkh Monolith of Shalmaneser III was discovered in 1861 by the British archaeologist J. E. Taylor, who at the time was serving as the British consul at Diyarbekir in southeastern Turkey. Taylor uncovered the monument at the site of Kurkh, modern Üçtepe, located near the upper Tigris River. It is one of the most widely known Assyrian inscriptions by Biblical scholars, because of its mentioning of the Israelite king Ahab who is recorded in the Biblical texts (1 Kings 16-22). Dated to 853-852 BCE it is the earliest extra-biblical source to testify to the King of Israel at its height. The Inscription lists Ahab as a member of an anti-Assyrian coalition that rose up after the death of Shalmaneser’s father Ashurnasirpal II, sparking a rebellion in the western region. The last narrated event on the inscription is the battle of Qarqar 853 BCE (Cogan 2008, 14-22). Therefore, we will see that the Shalmaneser’s Monolith not only corroborates the existence of Ahab but also reveals his geopolitical significance, military capacity, and participation in regional coalitions—dimensions largely muted or reframed by the biblical historian

King Ahab in The Biblical Narrative:

During the early stages of the Monarchic period, both the Southern and Northern Kingdoms of Israel and Judah were striving to find their place in the geopolitical sphere, and establish solidification of their identity. The Southern throne had been occupied by Asa for quite some time as portrayed by the author of 2 Kings, but the same could not be said for the North. After some tumultuous times of coup’s and usurpings against the throne, Ahab inherited the throne form his father Omri and managed to secure the throne for twenty two years according to (1 Kgs 16:30). His father Omri, while only briefly mentioned in the Bible, according extra Biblical sources the house of Omri became a label simply for the kingdom of Israel, bīt Omrī in Assyrian inscriptions. Thus was actually one of the most well known Israelite kings in the ancient word–likely because he established the city of Samaria as the capital of Israel, and set up its strong fortification. Ahab is painted in a negative light by the Historical scribe of Kings:

וַיַּ֨עַשׂ אַחְאָ֧ב בֶּן־עָמְרִ֛י הָרַ֖ע בְּעֵינֵ֣י יְהוָ֑ה מִכֹּ֖ל אֲשֶׁ֥ר לְפָנָֽיו

“Ahab, son of Omri, he did evil in the eyes of YHWH, more than all who were before him” (1 Kgs 16:30).

His approval of Baal worship via his Phoenician wife Jezebel, and his conflicts with the prophet Elijah are recorded in the last chapters of the book of 1 Kings. He had conflict with the king of Syria Ben-Hadad, who occupies what would’ve been territory of Northern Israel proper according to the legislation in the Torah. There war is recorded in 1 Kings 20 where Ahab is able to defeat Ben-Hadad in Aphek. In v34 a peace treaty is mentioned with Ben-Hadad promising to return the northern lands to Ahab. On these terms Ahab agreed. Yet the a Prophet of God condemns this treaty and the release of Ben-Hadad, carrying out a very powerful illustration of being struck, and then presenting himself to the king with a sharp rebuke (1 Kgs 20:35-43). After these events the narrator of Kings described the immoral murder of Naboth and taking of his vineyard by Ahab’s wife Jezebel. This is where external inscriptions help clarify the broader historical background to these narratives.

Insight into Biblical History:

To evaluate these biblical traditions historically, we now turn to Neo-Assyrian sources contemporary with Ahab’s reign. The Assyrian King Shalmaneser III took the throne of Assyria during the 9th century BC, his father Ashurnasirpal II had already been known as an ideological conquest king, and the west was apparently not too happy about this new Assyrian policy. When Shalmaneser III took the throne, he needed to campaign to the west to quash regional rebellion that was happening with Hittites, Syria, Egypt, and Northern Israel. This conquest is recorded in an inscription called the Kurkh Monolith. Here, the inscription records the kings great battle of Qarqar in the land of Syria. He lists the names of the kings and rulers that have formed what scholars like (Cogan 2008) have referred to as an Anti-Assyrian coalition. Guess whose name we find on this list of kings who aided Ben-Hadad or in Akkadian Hadu with chariots and men. King Ahab. Below is a translation provided by A.K. Grayson (1996).

Col. ii 89b-95

Moving on from the city Arganâ I approached the city Qarqar. I razed, destroyed, (and) burned the city Qarqar, his royal city. An alliance had been formed of (lit. “he/it had taken as his allies”) these twelve kings: 1,200 chariots, 1,200 cavalry, (and) 20,000 troops of Hadad-ezer (Adad-idri), the Damascene; 700 chariots, 700 cavalry, (and) 10,000 troops of Irhulēnu, the Hamatite; 2,000 chariots (and) 10,000 troops of Ahab (Ahabbu) the Israelite (Sir’alāia); 500 troops of Byblos; 1,000 troops of Egypt; 10 chariots (and) 10,000 troops of the land Irqanatu; 200 troops of Matinu-ba’l of the city Arvad; 200 troops of the land Usanātu; 30 chariots (and) [N],000 troops of Adunu-ba’al of the land Sianu; 1,000 camels of Gindibu of the Arabs; [N] hundred troops of Ba’asa, the man of Bīt-Ruhubi, the Ammonite. They attacked to [wage] war and battle against me (Grayson 1996, 22-23).

Thus, while confirming the Biblical narrative’s history, the Kurkh Monolith of Shalmaneser III simultanously provides one of the clearest extra-biblical synchronisms for the reign of Ahab by recording his participation in the coalition that opposed Assyria at the Battle of Qarqar in 853 BCE. In this inscription, Shalmaneser lists Ahabbu Sir’alāya “Ahab the Israelite” as supplying a military contingent, including chariots and infantry, and while the exact number on the inscription are debated–this places the king of Israel among the major regional powers resisting Assyrian expansion. This fixed Assyrian date anchors Ahab firmly in the early ninth century and confirms the biblical portrayal of Israel under Ahab as a politically assertive and militarily capable state which explains how he managed to rule for twenty two years. Moreover, the geopolitical context implied by the Monolith—Ahab cooperating with Ben-Hadad of Damascus against a common foe, corresponds with the biblical narrative in which Ahab alternates between conflict and alliance with Aram-Damascus.

Conclusion

Taken together, the Assyrian record and the biblical text mutually reinforce the historical situation of Ahab’s reign, demonstrating that the king described in 1 Kings fits precisely within the larger Near Eastern political landscape of the mid-ninth century BCE. The King would ultimately meet his demise when some time after this alliance was broken, Ahab convinces Jehosephat the king of Judah to attack Ramoth-gilead the kingdom of Syria, for not returning the lands as his father had promised. The King is lied to by his prophets due to a lying spirit sent by a divine counsel of YHWH who gave Ahab the approval to fight, where he was killed on the battlefield by a random arrow (1 Kgs 22:19-22, 29-40). Kurkh Monolith exemplifies how extra-biblical inscriptions can illuminate biblical history without collapsing the two narratives into one. Assyrian royal rhetoric and Israelite theological historiography serve different purposes, yet together they frame a historically credible portrait of Ahab’s reign. Such interdisciplinary intersections remain essential for reconstructing the ancient world of the Bible.

Kurk Monolith Stele British Museum 2025

Bibliography

Younger, K. Lawson, Jr.

“Neo-Assyrian Inscriptions: Shalmaneser III (2.113). Kurkh Monolith (2.113A).” In The Context of Scripture, Volume 2: Monumental Inscriptions from the Biblical World, edited by William W. Hallo and K. Lawson Younger Jr., 261–64. Leiden: Brill, 2000.

British Museum.

“Series: The Kurkh Stela (Shalmaneser III).” Museum no. 118884. Accessed December 12, 2025.

Grayson, A. Kirk.

Assyrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium BC II (858–745 BC). Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia Assyrian Periods, vol. 3. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996.

Cogan, Mordechai.

The Raging Torrent: Historical Inscriptions from Assyria and Babylonia Relating to Ancient Israel. 2nd ed. Jerusalem: Carta, 2008.

Leave a comment